A shorter (Hebrew) version

התפקיד הכפול של הסיפור הכתוב ומצוייר בהראת שפה נוספת למתחילים (2008). הד האולפן, גליון 94. עמ’ 84-94

of the original unpublished (English) paper below, was published in Hed Ha’ulpan 2008.

Table of content

1. Introduction

2. Story Time at the Vancouver Mini Ulpan

3. Vocabulary

4. Constructing Meaning – Practice versus Thinking

5. Graphic Semiotic Signs in Story Illustrations

6. Conclusion

7. References

1. Introduction

The beginners’ level of an additional language (L2) curriculum, limited in vocabulary and grammar, does not usually allow for much intellectually stimulating and enjoyable literary material, especially for adult students. Incorporating into the curriculum stories, which rely equally on their visual and verbal components, enables the beginners to construct relatively sophisticated meanings in spite of their very basic linguistic proficiency. The familiarity with now universal visual language with its common semiotic signs supports significantly the language imparted at this level. At the same time, this visual language, embedded in illustrations, allows the adult learner to construct richer meaning than that which is contained in the L2 text offered. The illustrations thus, provide livelier learning experiences more likely to enhance L2 acquisition than the otherwise mostly pragmatic, but, unfortunately, not too exciting beginners’ course material.

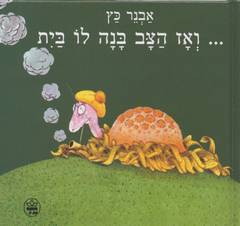

The following analysis is based on work done at Story Time hours of the beginners’ level of the Vancouver Mini Ulpan (a week-long, 25 hours, intensive Modern Hebrew course) (Halabe, unpublished). The text used is the level appropriate, adapted version of Avner Katz’s story ואז הצב בנה לו בית… ( … And then the Turtle Built himself a House) together with its original illustrations.

To see these illustrations (in small size) click on Turtle1 – illustration & Turtle2 – illustration

Katz’s story can be described as a multimodal text (Royce, 2002). It relies equally on the verbal and the graphics which reflect, as well as complement each other. Much of the story line can be understood without words through the very humorous and colourful cartoon-like illustrations. The original Hebrew text of the story, though, is much beyond this beginner’s level. The original story uses all tenses, rhymes and mixed registers. Therefore, and in order to adjust it to the beginner’s level, the text was completely rewritten and infused with basic vocabulary and grammar compatible with the language objectives of this basic level curriculum.

What is the potential of illustrations, and especially cartoon-like ones in the L2 beginners’ curriculum?

Visuals are commonly incorporated into L2 learning material. They are usually used as graphic signifiers parallel to specific verbal signifiers taught (e.g.: illustrations of an apple, a chair or a flower, while teaching the respective words), more complex and detailed pictures (e.g.: a picture of a market) to help impart the language revolving around certain subjects, or illustrations depicting a narrative. Encouraging the students to learn from visuals can activate the their background knowledge and thus reduce, so-called, text shock. By using the image to get some idea of what to expect, students can ease themselves into a reading” (Royce, 2002).

The objective of using illustrations in the Beginners’ Mini Ulpan is twofold. Avner Katz’s original story illustrations are presented to the students together with every passage of the rewritten Hebrew text in order to:

· support students in their attempt to grasp the more concrete language reinforced and imparted through the text, and to comprehend the story line.

· provide, through visual language, information beyond that which is apparent in the limited, basic vocabulary and grammar in the Hebrew text presented. Through the added illustrations students can construct meaning on a higher level of complexity and interest, even if not essential for their L2 learning.

2. Story Time at the Vancouver Mini Ulpan

Story time occupies the last of the five hours of the Mini Ulpan day. Its presentation to students is designed to reinforce the basic grammar and frequent vocabulary imparted in the earlier hours of the day. No new grammar is introduced through the story. A small number of new words though, are introduced, mostly frequent ones.

In each of the 5 daily sessions of Story Time the teacher reads aloud a passage. The students listen first to the reading without following the text. They are expected to listen and try to construct meaning. In this first, animated reading the teacher stops often to point to the illustrations and to pictures in the course scrap book. The teacher uses expressive body language and tone, paraphrases, and refers to vocabulary used in earlier hours of the day. All the above provides the extra-linguistic context helping in decoding the language imparted, reviewed. This extra linguistic context is crucial for language acquisition (Krashen, 1985. p. 4-5), English is used rarely and only as a last resort. The story is told, while constantly ensuring students’ comprehension of the storyline. The students are encouraged to venture at ‘educated guess’ with the help of the already learned vocabulary and grammar, the context, and the familiar semiotic signs and depiction of the narrative in the illustrations. Following this first presentation, the teacher reads the text aloud for the second time in the same animated way, pointing to illustrations, but attempting to do so with much less explanation. This time students follow the text, and even join the teacher in reading it allowed. The reading is followed by the students retelling of the story in Hebrew. Still later they try to apply the language learned in conversation around other similar topics. The response to the Story Time part of the Mini Ulpan is usually very positive.

I would like to argue that students benefit from and satisfaction with the Mini Ulpan Story Time is due not only to the well controlled vocabulary and grammar incorporated into the rewritten story, but also to the double roll of the story illustrations offered. Through Story Time, level appropriate pragmatic L2 material is delivered and reinforced, and at the same time an intelligent, adult appropriate construction of meaning is allowed. The more sophisticated meaning constructed (albeit from visuals and not through L2), contributes to a higher sense of achievement.

A major psychological difficulty for the adults learning a new language is the frustration of having to bear with the inescapable utilitarian texts. Because of the initial level, these texts are of very poor, if not boring content. Offering a literary text at Story Time is one of the more effective ways in easing this frustration (Halabe, unpublished). The artistic, interesting multimodal (albeit uneven) text which allows for more complex construction of meaning is more enjoyable, creates a positive atmosphere and thus, conducive to adults’ further learning.

The make up of the rewritten story and the corresponding original illustrations of Avner Katz will be analyse below. The analysis will be helpful in understanding the interaction between the verbal and the visual, and their contribution to L2 acquisition and to the creation of an atmosphere conducive to adult learning.

3. Vocabulary

The Mini Ulpan program relies heavily on frequent vocabulary. Thirty one Hebrew verbs were chosen for the beginners’ level for their frequent appearance in every day talk and classroom situation. Another consideration in choosing verbs for the beginners’ vocabulary was the attempt to present a relatively wide range of Hebrew root and verb stem morphology. A good number of the chosen are useful as grammatical models for further learning. The Hebrew verbs chosen are:

אכל, שתה, עשה, אמר, דִבר, הלך, בא, ישב, רצה, אהב, ראה, שמע, נתן, למד, ידע, הבין, חשב,קרא, כתב, גר, עבד, התעמל, התחיל, המשיך, נכנס, נשאר, שר, נִגן, שִחק, בנה, חִפש.

[eat, drink, do/make, say, talk, walk/go, come, sit, want, love/like, see, hear, give, learn/study, know, understand, think, read, write, live/reside, work, exercise (sport) start, continue, enter, stay, sing, play (music), play, build, search]

.

Twenty verbs, 65% of this list (see above in bold) were incorporated into the rewritten Turtle story offered at Story Time.

Similarly, 15 Hebrew adjectives, more than 50% of frequent adjectives offered in the course, were incorporated into the story:

גדול, קטן, רחב, גבוה, טוב, שמח, חכם, צעיר, עצוב, כועס, חם, קר, יפה.

[big, small, wide, tall/high, good, happy, wise, young, sad, angry, hot, cold, beautiful.]

The same was done for other word categories (nouns, conjunctions etc.).

As obvious from the above lists, Israeli frequent Hebrew vocabulary is very similar, if not close to identical, to frequent English vocabulary, or to frequent vocabulary of any other language (used in modern, westernized urban setting), for that matter. Even if semiotically expressed differently, the signified of words appearing in frequent words lists, are basic to every day human life (eat, drink, big, small, home, work etc.). Thus, the students are not introduced to new concepts. Beginners’ level of any L2 course relies to a large extent, therefore, on what Cummins would define as “common underlying knowledge” (Baker, 2001. pp. 165-166).

As shown above, the rewritten text of Avner Katz’s story is infused with much of the vocabulary chosen for the beginners’ course. It is also peppered with some words not originally Hebrew, but commonly used in Modern Hebrew: July, August, January, February, university, sandwich, coffee, tobacco etc. The use of foreign vocabulary is helpful in avoiding, at this elementary stage, the use of less needed words (e.g.: July & August, instead of ‘summer’ ) and the expression of more complex ideas (e.g.: coffee, tobacco and arugula, to express the pretension of the budding, yappy architect). Also, the students have to concentrate intensively on the recently learned Hebrew vocabulary and grammar; While listening to the story they are granted with short instances of relief when they encounter some words familiar from their first language.

4. Constructing Meaning – Practice versus Thinking

The purpose of the vocabulary incorporated into the rewritten Turtle story offered in the Mini Ulpan Story Time, is the practice and reinforcement of the language recently introduced, and not the teaching of a subject matter (in this case, a literary work). Therefore, while adapting the original text, only the very general story line was kept. Details were deleted or changed, and other, albeit superfluous, details were added as a vehicle by which the level appropriate vocabulary and grammar has been applied. Indeed, this adapted text does not have much literary merit. It is very wordy, contains many repetitions, and barely keeps the succinct humoristic style of the original work. Nevertheless, its entertaining qualities are kept mostly thanks to the accompanying illustrations, which will be discussed later.

Practice

Illustration 7 depict the return of the young Turtle from University(To see it, click on Turtle1 – illustration) .

Clicking on illustration 7 texts comparison you will find a table comparing between the original text and the rewritten text of this illustration demonstrating well the difference between the two.

The objective for creating the adapted text for the 7th illustration was to practice some new vocabulary, the Hebrew numbers, and the Hebrew Infinitive, which were all taught in the earlier hours that day (The third day of the beginners’ course). The adapted text is therefore, excessively lengthy, but very effective for the practice of the language being learned

The illustrations presented simultaneously with the story, serve thus, first of all to support the students in their interpretation of the text offered. Every scene and passage of the text is read while constantly referring and pointing to the parallel illustration. The illustrations provide therefore additional helpful signifiers, this time graphic, to the L2 audible or written signifiers. Thus, while hearing the new word צב (‘tsav’) and seeing a graphic depiction of the word, pointed to  on the book cover, the student can decode the audible signifier as the Hebrew equivalent of the English word ‘turtle’.

on the book cover, the student can decode the audible signifier as the Hebrew equivalent of the English word ‘turtle’.

Thinking

But, as already mentioned above, the roll of the illustrations used in the Mini Ulpan Story Time, is beyond the decoding of the concrete and the basic plot. Avner Katz’s original work, relies equally on his humorous text and funny cartoon-like illustrations. Without the illustrations and the original Hebrew text, the rewritten text certainly lacks the original artistic qualities. Its utilitarian adaptation is indeed very effective within the curriculum of a beginners’ Hebrew course. This pedagogically sound, adapted text however, would not be able to entertain the students, or give them the sense of encountering a thematically more substantial and sophisticated text. The adapted text succeeds in doing so, only thanks to the original illustration used to accompany its presentation.

The illustrations offered simultaneously with the rewritten text, offer the students a richer experience than the pragmatic, pedagogically sound text on its own. The illustrations allow for a more thoughtful processing of the story than would be possible just through decoding of the L2 words. The illustrations include information, or allow interpretations, not necessarily included or implied in the simplified basic-Hebrew text on its own. I argue, therefore, that presented with the story in both its simple, level-appropriate version and its illustrations, students would be able, if asked, to retell the story in their first language (L1) in a more complex way than the adapted text does. Their constructed story in their L1, even though much more succinct, would be more layered and expressed in a more refined and accurate language. Thus we will be able to conclude that the combination of the rewritten text with the illustrations activates a higher intellectual level of thinking.

In order to find out if, indeed the meanings that can be constructed from Avner Katz’s illustrations are beyond the concrete, pragmatic meaning conveyed through the adapted text, three English speakers (not students in the Hebrew course) were presented with the illustrations without any text. They were asked to give their interpretation and retell the story. The only verbal clue provided was an English title: “How the Turtle Got His House”. Their interpretations of the story (see appendices 3, 4, 5) provide us with much insight to the difference between the L1 language activated and the thinking elicited by the illustration versus the L2 language used in the text offered at Story Tim

Meaning Constructed from Illustrations versus Simplified Text

Let us start by looking at the verbs used in these 3 English interpretations and compare them with the verbs used in the rewritten Hebrew text presented to the beginners students:

A good percentage (30%-50%) of the frequent verbs imparted in the beginners Hebrew course (see above p. 6), appear among the verbs used by the three English speakers in their retelling of the Turtle story. These are simple, more general, indiscrete verbs such as: ] עשה, אמר, דִבּר, הלך, בא, עבדdo/make, say/tell, talk, walk/go, come, work]. They appear frequently in the rewritten Hebrew Turtle story, but much less so in the three English interpretations (only 21%-29% of all the verbs used). Most of the verbs used in the English interpretations (71%-79%) do not have their parallel among the Hebrew course verbs.

.

Interpretation No.1 verbs (verbs corresponding to Hebrew course verbs in bold):

suffer, meet, search, know, build, find, leave, go-to-do, come, seem, change, figure, going-to-be, start, plan, show, think, allow, make, end-up, work, banish, walk-off, go-away, realize, get, loose, humble-down, measure, smile, cast, present, like, adopt, crawl.

.

Interpretation No. 2 verbs

sweat, cover, expose, discuss, go, find, build, protect, discover, ask, design, leave, get, rush, work, show, complete, look, realize, send-away, cry, start, sit, feel, fail, begin, take, measure.

.

Interpretation No.3 verbs

sweat, start, pour, grow, talk, walk, confront, play, tell, leave, return, work, look, show, over-look, reject, sit, think, take, measure, come-up, convince, wear, join, get.

The verbs used in these three English interpretations which do not correspond to the simple verbs used in the Beginners’ Hebrew text are more designated, accurate. Thus:

instead of (or together with) the more general, simpler verbs אמר (say/tell) or דִבר (talk) in the beginners’ Hebrew text, we find in the English interpretations for similar context, the more sophisticated and varied verbs: meet, discuss, ask, confront, reject;

instead of עשה (do/make) or בנה (build) – design, plan, cast.

instead of חשב (think) – figure, realize, come up with.

instead of הלך (walk/go), בא (come) – return, rush.

etc.

The language in the three English interpretations is richer than the one in the simplified Hebrew text. This is apparent not only through the verbs, but also in a more varied use of tenses, nouns, adjectives, idioms, prepositions etc.

As the three English interpretations are based on the illustrations only, their story lines are of course not identical to the original Hebrew story or its simplified version. Much of their language though, would certainly not be considered basic (the required vocabulary for a beginners’ L2 level of any language). For example:

Concrete Nouns: plants, building-blocks, building, studio, arm-span, draft, shell,

elements, prodigy, desert, persona, prototype, factory, masterpiece, scarf, tape-measure, parameters, angle pattern, mould, , palace, design, equipment, group, top of a mound, body

Abstract Nouns: plans, epiphany, huff, fruition, result, business, condition, mind, trouble,

Adjectives: industrious, nervous, upset, fancy-shmancy, physical, various, impractical, formal

Adverbs: doubtfully

The three English interpretations are not as wordy as the simplified Hebrew text. It is similar in length to Avner Katz’s original text. The permission to use a first language though, allows for wider range of verbal options. Here is how they interpret the same illustration (No.7) described above:

Interpretation No. 1: He comes back with a lot of plans. Seems to have changed his persona. He figures he is going to be a big ‘macher’ (big shot) now.

Interpretation No. 2: He or she rushes back to the business tortoises with various plans for designing a building.

Interpretation No. 3: The turtle returned, this time industrious with building plans.

Other than the simple, indiscreet vocabulary and the limited grammar (present tense only) the utilitarian Hebrew text offered to the students is pragmatic. The L1 used in the three English interpretations, on the other hand, is richer, more discrete and refined and allows more complex elaborations on topics beyond the pragmatic: motivations, feelings, satire, symbolism, etc. Here are few more examples drawn from the English interpretations:

The tortoise is exposed to the elements or suffering from the elements.

…seems to have changed his persona. He figures he is going to be a big ‘macher’

… starts to plan his masterpiece… his dream house

The business tortoises look doubtfully at the building

…feeling sad because he failed.

…Then he gets a Eureka idea. He looses his scarf while thinking, which means he humbles down.

The English interpretations show that the illustrations include a plethora of graphic semiotic signs signifying not only the concrete but also abstract notions. The English speakers were not limited to basic L2 vocabulary and grammar, and were able to interpret this visual language easily and express their interpretation in relatively rich vocabulary. The English speaking students learning Hebrew are presented with a lengthy but simple, even dull, adapted Hebrew text. At the same time they are presented also with the original illustrations from which they can derive rich information and insight, and construct meanings, no less complex than in the three English as a L1 interpretations.

5. Graphic Semiotic signs in the Story Illustrations

What are the graphic elements in Avner Katz’s illustrations acting as semiotic signs supporting the comprehension of the adapted Hebrew text and eliciting thinking (albeit in L1) beyond the concrete and beyond its content. Graphic elements found in the illustrations were identified and their accepted meanings determined. The following examples demonstrate how graphic semiotic signs can be understood as signifiers of both the more concrete or of the more abstract. Indeed, the distinction between the more concrete and the more abstract is not sharp. This is therefore, a very rough categorization, but should be regarded as adequate for this exploratory paper. Still, the distinction is helpful in demonstrating the different levels on which a graphic signs may be interpreted.

As demonstrated by the three English interpretations, even the illustrations on their own are capable of delivering much of the story line without language. This is of course the greatest advantage of using a good multimodal work such as Avner Katz’s for the beginner’s level. The illustrations contain a large number of semiotic signs common to both Hebrew and English speakers. As they are part of their background underlying knowledge, such graphic semiotic signs can certainly ease students into listening and reading the text with comprehension. The by now, universality of such graphic signs, which has created a common visual language, is evident from the examples retrieved from theMicrosoft Word Clip Organizer and compared with Avner Katz’s illustrations. Click clip illustrations:

Familiar semiotic signs such as the above, may depict the more concrete as well as the abstract. They help the students form a schema of the story with which they can approach both their initial listening to a text and later to their reading. At the same time they may contribute extra information not necessarily appearing in the text which may add to the texture and complexity of the work used and enhance the students’ enjoyment from it beyond its utilitarian purpose – teaching an additional language. An excellent example in our story is the following graphic intertextuality used by Avner Katz. His illustration No. 17 (to see it click on Turtle2 – illustration) depicting the blueprint for the final suggestion for a turtle house echoes Leonardo Da Vinchi’s Golden Ratio sketch

None of the three L1 speakers, who provided the English interpretations, were aware of this intertextuality. However, in the Mini Ulpan courses there are always those who identify the ‘quoted’ sketch. For them this is one of the highlights of the story, providing them with a sense of entertainment and pride in their self image as intelligent, cultured people. This is an opposite extreme to the discaraging infantalization often experienced by adult beginners in L2 courses, which hinders at time their motivation to continue. Cartoons and cartoon like illustrations often contain hidden jokes not necessarily corresponding or referred to in the written text. People the world over are now familiar with this genre and would appreciate incorporating it into the beginners’ additional language course material. It can enrich their learning experience, otherwise limited to the narrowly pragmatic.

6. Conclusion

) “ואז הצב בנה לו בית”“…And then the Turtle Built Himself a House”) is presented to the adult learners at the Hebrew beginners’ level of the Mini Ulpan, stripped off its satirical, succinct and playful original Hebrew text. It is replaced by, admittedly, a lesser text from a literary point of view. However, the rewritten story still keeps much of its original qualities, mostly through its untouched illustrations. As a multimodal text, constituting of the sophisticated original illustrations together with the rewritten, level-appropriate simplistic text, it fulfills its double roll for the Mini Ulpan students: it helps them practice the newly learned Hebrew vocabulary and grammar, as well as activates a higher level of complex and abstract thinking and allows them to construct meaning beyond the constraints of an introductory L2 level. Through this uneven multimodality, with its visual half stronger, than its pragmatic verbal half, the students can construct a more interesting, layered story. This intellectually much more satisfying experience is certainly more enjoyable than just the decoding of L2 adapted text. It also grants the students with the reassurance, countering the possible unsettling feeling of ‘infantalization’, experienced by some, and caused by their still very limited L2 lexical and grammatical competence. This enjoyable and stimulating atmosphere, created at Story Time, is no doubt, encouraging and conducive to adult learning.

Multimodal texts, with their visual language much more sophisticated than their verbal language, can provide the adult students with both the adequate L2 practice, and with a relief from the pedagogically effective, but mostly poor content material, almost unavoidable in the very early linguistically restricted stages of basic L2 learning.

Uneven multimodal text can exploit more fully the ‘common underlying knowledge’ claimed by Cummins to help with the learning of L2 (Baker, 2001. pp. 165-166): Familiar, now almost universal, visual language with its graphic semiotic signs found especially in cartoons and cartoon like illustrations, can activate a plethora of knowledge and information which supports and adds on the comprehension of L2 texts offered. Few areas of common underlying knowledge were identified through the discussion of the Turtle story: everyday concrete objects and concepts, more complex and abstract concepts and thinking processes, and even literary-artistic genres. Such areas of common underlying knowledge, expressed by visual language, can help the students construct the expected meanings in L2, but also add extra meanings, albeit not in L1 thinking, to enrich their learning experience.

In order to complement the pragmatic material used in introductory levels, L2 teachers should be encouraged to look for similar cartoon-like, multimodal works. They can adapt them to the needs of their students, using them as vehicles for the transmission of L2 level-appropriate required vocabulary and grammar. The sources for such material may be works originally intended for adults, but also good ‘ambivalent’ works created for children (Halabe, 2006). Multimodal works may be found in various cartoon genres such as satire, romance, fantasy and science fiction. Their text may be heavily altered and adapted to fit the requirements of the elementary beginners’ level, but their original illustrations should be kept intact to provide the support as well as the richer experience.

References:

Baker, C. (2001). Foundation of bilingual education and bilingualism (3rd ed.). Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Halabe, R. (2006) Hebrew children’s literature and the adult second/foreign language learner Hebrew Children Literature and the Adult Learner of Hebrew as a Second/Foreign Language

כץ, א. (1979). …ואז הצב בנה לו בית. ירושלים: כתר

[Katz, A. (1979). …and then the turtle built himself a House. Jerusalem: Keter.]

Krashen, S. 1985. The imput hypothesis. London & New York: Longman

Royce, T. (2002). Multimodality in the TESOL classroom: Exploring visual-verbal synergy. TESOL Quarterly. Vol. 36, No. 2, 191-205.