Note: the following paper (English) has not been published. A shorter article based on it, was published in Hed-Haulpan 95: ‘ספרות ילדים בהוראת שפה נוספת למבוגרים

Hebrew Children’s Literature and & the Adult Learner of Hebrew As a Second/Foreign Language

Rahel Halabe

Table of contents

1. Introduction

2. Literature in Second/Foreign Language Teaching and Learning

3. Children’s Literature in the Adult Second/Foreign Classroom

4. Children’s Literature and the Adult Reader

5. Hebrew Children’s Literature

6. The Potential of Hebrew Children’s Literature for the Adult Students

7. Story Time in the Vancouver Mini Ulpan

8. Four Hebrew Children Stories

9. Conclusion

10. References

1. Introduction

Teaching an additional language (a second or foreign language) to adults starts by focusing on ‘pragmatic’ or everyday language. Ideally this practice integrates the most frequently used vocabulary and grammar in order to give the student an optimal mix of the simple with the practical. Language that describes feelings, thoughts and opinions is postponed to later stages. Unfortunately, similarly postponed are students’ opportunities to enjoy valuable works of literature. For example, many Hebrew textbooks available today for the beginner adult learner, are thoughtfully planned and graduated, as well as skilfully written. They are much livelier than they used to be. The content of these textbooks though, is still mostly pragmatic. Students must be satisfied for a long time with textbook written material, which in spite of its pedagogical merits, lacks the artistic value found in works of literature. Students also have to wait long before they encounter subjects with which they can engage on an adult level and that have a more thoughtful depth than just dealing with day to day practicalities.

This paper suggests the idea of integrating more inspiring material drawn from children’s literature into the curriculum of the adult Beginners’ and Low Intermediate levels of additional language (L2 ) curriculum. Even though such literary work was not originally written for teaching purposes, or even primarily for adults, it could possibly provide the students with a pleasurable support for their learning of frequent vocabulary and grammar. Through the study of these works, students could also learn effective strategies for listening and reading with comprehension. It could offer them opportunities for going beyond the usual limited scope of subjects possible at their level, and so potentially, they could begin to express feelings and opinions, as well as to discuss them, albeit in a simple manner. Moreover, much of the authentic, even if adapted, material, written originally for young readers, contains a significant cultural component. Therefore, it could open to adult students a window into the culture of the language they are learning.

All the above is certainly relevant to the teaching and learning of Modern Hebrew. Modern Hebrew children’s literature is rich and versatile. If chosen and incorporated appropriately into the curriculum, it can reinforce and enhance the adult students’ learning, as well as offer them many glimpses, not only into Modern Israeli, but also traditional Jewish culture.

This paper draws much support, information and insight from children’s literature research as well as from language acquisition and Second/Foreign (SL/FL) teaching methodologies. The paper also relies heavily on my practical experience as a teacher of Classical and Modern Hebrew, and especially on the work I have done in the Vancouver Summer Mini Ulpan, experimenting with the introduction of children’s literature to the students of three levels. In this paper, I will describe these intensive courses, with their important Story Time component. Finally, some suggestions for further work in this direction will be offered.

2. Literature in Second/Foreign (L2) Teaching and Learning

The value of literature for the L2 learner has been recognized, but not necessarily widely acted upon. Historically, studying literary canons was the focus of the study of classical languages. The study of modern languages, as foreign languages, has also emphasised literature. It was only in the second half of the twentieth century that the focus shifted sharply from literature, to communication and pragmatics. The renewed interest in bringing literature back into the L2 classroom is not necessarily for the sake of studying literature, but instead as a medium, through which students can be exposed to the culture in question, as well as expand their vocabulary and have an opportunity to exercise their conversational skills. (Onestopenglish, 2005). However, authentic literary texts (novels, short stories and poems) are used mostly in the more advanced levels.

A look at Hebrew University Ulpan (immersion courses) textbooks for beginners and lower intermediate students shows that they do not lack in classical and modern pieces of literature (prose is usually adapted, whereas poetry is included as is). The Ulpan method is based on the communicative-pragmatic approach. These enriching texts are suggested material only, not an integral part of the curriculum . They are offered in order to expose the students to authentic texts and urge them to read while making courageous educated guesses about meaning. (Hayyat, Yisraeli, & Kovliner, 2000-2001).

Interestingly enough, textbooks written in the Diaspora, give more emphasis to text than to communication. For example, in Ivrit Shalav Guimel (Band, 1986) prose pieces, half of which are simplified literary works, are the starting point for each of its lessons. Here too, the poems offered are introduced without adaptation. Some of the literary texts offered were originally written for adults and some are taken from children’s literature. Another textbook, Ha-Yesod includes texts which are taken mostly “from the treasure of the Jewish culture in all its layers. The material was rewritten and suited for the demonstration of the grammatical forms of that lesson” (Uveeler & Bronznick, 1972, p. v). These texts are integral to the teaching of lexicon and grammar in this textbook. They are therefore heavily adapted to be compatible with the level of each lesson. They deal with historical Jewish personalities and historical events, and retell biblical, midrashic, and hassidic stories. This content, in its simplified manner, would be close to similar genres in Hebrew Children literature.

As mentioned above, literature is not a common integral part of the lower level communicative-pragmatic approach curriculum. It is taught as part of the curriculum in Ulpanim (immersion programs) only in the higher levels. An interesting attempt to include literature of absurd humoristic qualities, in six levels of ulpan program, including the lower ones, made use of works by the renowned Israeli playwright, Hanoch Levine. This was done, explain Weis and Abadi, because humour creates a relaxed learning atmosphere, is a good communicative medium and allows for easier grasp and retention of the material. Surprisingly, they managed to find among Hanoch’s writings, pieces written originally in relatively simple language, suitable even for the lower levels. The pieces they use offer both level appropriate lexical and grammatical subjects for teaching and a variety of options for post reading activities (Weis & Abadi, 2003).

Adult literature is studied in the L2 classroom mostly in the advanced level. For students in a lower level, such material would pose great difficulties due to length, complicated plots, complex characters and ideas, many details, descriptions, digressions and difficult language. Usually, adult literature can be offered in the lower levels only if heavily adapted. Students therefore, do not have the opportunity to enjoy real works of literature of the culture whose language they are learning until much later.

3. Children’s Literature (CL) in the Adult Second/Foreign Language Classroom

Adult literature may indeed be unsuitable for the lower L2 classroom due to students’ limited repertoire and classroom time constraints. Children’s literature, however, may offer these students the pleasure of reading real works of literature much earlier on. Some educators might reject this material based on the assumption that adult students expect mature material. They would question why should childish texts be used as an integral part of the curriculum, when there is so much good material, prepared especially for the purpose of L2 teaching. Indeed the variety of textbooks and their rich content, as well as other modern learning materials, make the teaching and the learning of L2 today much easier. Textbook material may be a good and effective in imparting the lexicon and the grammar. Still, it cannot compete with the depth, inspiration and artistic qualities which can be found in literature. Adult literature is beyond low level students’ grasp in the newly learned language. Therefore, adult students have to bear with utilitarian material, tailored exactly to each lesson and the lexical and grammatical subjects it imparts. For a long time adult learners either enjoy or do not enjoy the made-up stories, with their, at times, forced humour. They have to wait patiently for much more advanced stages, when they can encounter a meaningful piece of authentic fiction or non-fiction as an integral part of the curriculum. In the meantime, the suggested children’s literature (CL), much of which is good literature, can offer an appropriate lively addition to effective, but often uninspiring textbook material.

Acknowledging that “When learning is pleasurable, a greater learning takes place”, Gayle Flickinger reviewed a number of American children’s books and analyzed their potential to enhance adult ESOL students. These stories provide the students with the opportunity to improve on their reading, give them glimpses of the American customs and culture, and allow them to express themselves through meaningful universal issues which transcend cultures (Flickinger, 1984).

The use of CL in the development of English literacy in elementary students, both with native and non native speakers, has been successful. Subsequently it has increasingly been tried with adult students as well, especially in ESL family literacy programs. The selection of books should consider age-appropriate themes, compatible language level, learning enhancement style, illustration and cultural input, as well as clear class presentation and development of related lessons, are essential to the success of such attempts (Smallwood, 1992).

In spite of a few limitations, children’s picture books and short stories were found to be very effective in the lower levels of English as a foreign language for Chinese university students. Even though relatively simple, and probably because of that, they motivated the students and were used for pronunciation exercises, reading practice, discussion and expression of opinions. They stimulated literary appreciation and comparison between Chinese and English literary practices. Themes in stories were discussed seriously and at times even understood as symbolising political issues relevant to students’ life. The stories were “intellectually stimulating, encouragingly readable, linguistically challenging, literarily fulfilling, and educationally rewarding”. They were a good stepping stone to confronting more mature material, and saved the students the deterrence of the sophisticated linguistic style, themes, or unfamiliar genre, if introduced too early (Ho, 2000).

Indeed, good CL which is as meaningful, artistically written, and enjoyable as adult literature, still has specific features which make it appropriate for its integration into L2 lower levels curriculum.

Material written for children tends to revolve to a large extent around a child’s life and world. Therefore, it uses much of children’s vocabulary which overlaps greatly with frequently used adult vocabulary. Learning the most frequent vocabulary is extremely important in the acquisition of L2, as it covers most of the word count of any oral or written text (Haramati, 1983, p. 109). The use of children’s literature can impart such words as well as support the retention of others previously learned. The significant appearance of frequent everyday vocabulary in children’s literature does not mean necessarily that the work is simple or unsophisticated or that it cannot use more literary register. At the same time, even if such register is used, the language in children’s literature would still be less complex than in a text written for the adult. It can therefore be a good introduction to literary writing for the lower level student

As in songs and poetry, much of young children’s literature uses extensive literary devices which facilitate language learning at any age. Repetition, rhymes, and imagery make it easier to memorize sentences and passages. Memorization, or near memorization, helps familiarize and probably even internalize certain word formations (i.e., verb conjugation) and syntactic patterns characteristic of the language learned.

However, simple features do not necessarily imply simple content. As described below (Chapter 4), CL may deal with serious human issues in a deep way, albeit in a simple form. A good work of literature, written for any age, cannot be grasped fully at first glance. A good story or poem gradually reveals its many facets and layers only with repeated readings and depends on the different aspects of a reader’s level of development such as age, life experience, reading experience etc. (Elkad-Lehman, 2003). Stories that may seem naïve at first glance, can be interpreted differently, at times in an unexpected way, by different readers of different backgrounds. Children’s stories can thus raise interesting, mature subjects suitable for adult discussion. They can provide opportunities for students to talk about feelings and express opinions in various subjects. Even while using basic vocabulary, students are able discuss not only practical subjects (work, housing, food etc.), but even more general ones (i.e., social, economical, political, and moral).

Subjects found in CL may transcend cultural differences and allow the students the comfort of dealing with familiar universal questions through the newly learned language. At the same time, the setting of these subjects in children’s texts may highlight the differences between cultures, inform the students and provide them with insights about the target culture, its reality and its values.

Illustrated stories and picture books in particular can be most suitable for integration into lower level L2 programs. Visual material has been shown to enhance listening and reading comprehension, providing the student with organizational schema for the text (Omaggio-Hadley, 2001, p. 150).

A good measure of humour, found often in children’s literature, can contribute to a relaxed learning atmosphere and may even ensure better retention of the lexical and grammatical subjects learned. If carefully chosen, works written for children may offer another layer of comic messages for the secondary addressee, the adult (see below chapter4).

L2 textbook material, tailored for specific lexical and grammatical subjects imparted in a lesson, are usually studied intensively to ensure full comprehension. This though, should not be the treatment of a children’s story introduced in class. It is important to clarify to students that in order to capture the plot, the characters, and the basic ideas, they do not have necessarily to understand every word and every grammatical item appearing in the text. Students should learn how to get the gist of a text that they listen to or that is read by them. Adopting appropriate strategies (such as filling the blanks and educated guessing) helps them cover a complete story and even discuss it in a much shorter time and a much more gratifying way, without having to dwell on it to the point of boredom. Moreover, the less intensive treatment of a children’s story may empower the students and lead them to a stage in language learning in which they will feel confident enough to confront a text or a conversation they don’t completely understand. The introduction to the story in class, together with further rereading and re-listening at home, can encourage the students to embark on further independent and extensive, level-appropriate reading and listening. Such out-of-class exposure to the language is most important for progress into higher levels, at times even more than further class input, as it draws the students closer to the ‘real’ language

Story telling, which for ages has captured the attention, not only of children, but of adults as well, has been replaced in our era by individual quiet reading and the un-interactive watching of screens. Surprisingly, adult students enjoy very much listening to an animated presentation of a story offered to them. One should bear in mind though, that stories may have unexpected great psychological or intellectual impact on listeners and readers. stories are used creatively and effectively in bibliotherapy (Cohen, 1990), drama therapy (Golan, 1983), and various communication workshops, in order to help participants open up to dealing with difficult, even painful personal issues, as well as for analysis of situations and for expressing opinions. Indeed, CL provides the L2 students with ample opportunities to present their point of view as well as their feelings about topics raised by the stories. Teachers should be extremely careful though, not to let the discussion and openness overflow beyond reasonable proportions. They should be sensitive and keep remembering, even reminding their students, that the main purpose of the lesson is learning the language and its culture in a pleasurable way and not delving into dangerously deep emotional, moral, political and other grounds. One of the ways to avoid extreme reactions is assign various roles to different students in order to present different points of view or emotional stands.

All the above shows that CL has the potential of contributing much to enliven the L2 curriculum of the lower levels, enrich students’ language skills and introduce them to the culture whose language they are learning much earlier on. A detailed description of Story Time in the Vancouver Mini Ulpan will demonstrate that (see chapter 7).

4. Children’s Literature and the Adult Reader

Children’s literature has indeed educational, pedagogical and psychological importance for the welfare of children. Moreover it should be regarded “as literature per se… a part of the literary system…an integral part of society’s cultural life”. Children’s literature reflects the general patterns of behaviour in the literary and cultural context from which it has developed (Shavit, 1986, pp. x-xi).

The various literatures, or systems, in any literary polysystem tend to overlap and intersect (Even-Zohar, 1990). Various aspects of children’s literature such as text types, styles, themes, ideologies, and appeal to different groups of readership, are similar to other kinds of literature. Genres such as historical novels, humour, fantasy and science fiction have juvenile versions for younger readers. Books are also often read by readers for which they weren’t intended. For example, books such as Robinson Crusoe and Gulliver, were originally written for adults, and have been adopted by children, whereas The Little Prince and Alice’s Adventures, were written for children, but are also read by adults. Many adult readers continue to read favourite books of their childhood and youth, long after growing up, and find in them not only a nostalgic sense of comfort, but even deeper insights and layers with every additional reading. At the same time, fairy tales, which were originally created for and enjoyed by all ages throughout history and all over the world, are offered now, especially in the Western world, mostly to children.

Fairy tales, as has been outlined by Bruno Bettleheim, are still important for adults. Indeed, they often simplify situations and deal with them briefly and pointedly. These stories broad strokes important details are used to present characters that are typical, rather than unique. Yet, these stories also deal with universal human problems, which they convey through overt and covert meanings “in a manner which reaches the uneducated mind of the child as well as that of the sophisticated adult” , addressing the conscious, the preconscious, and the unconscious, thus enriching and satisfying all ages (Bettelheim, 1976, p. 5-8).

Many modern children’s stories follow folk tale characteristics and qualities and thus, have a similar impact. Under the surface of what could be perceived at first glance as a simplistic story, the reader of CL may encounter serious social, emotional and existential problems and dilemmas concerning good and evil, loss, fear, identity, straggle, choice etc. For example, Robert Munsch’s, The Paper Bag Princess uses the familiar features of fairy tales, including repetitive structure, humoristic presentation, and age-old motives of the courageous smaller or weaker protagonists and their victory through their wits over the cruel and powerful. The model of the traditional fairy tale, skilfully manipulated, allowed also for the introduction of current feminist dilemmas, ending with a counter formula happy ending.

The content of children’s stories, as well as the artistic presentations are not necessarily childish. Children’s literature should be well-written and pleasurable reading for both the child and the adult, agree two of the most important authors and scholars of Hebrew children literature (Goldberg, 1977, p. 67. Roth, 1969, p. 11). Children can find themselves and their own troubles in stories. At the same time, they experience through stories “birth and death – love, hate, heroism, courage and fear” and in fact, their culture’s life patterns and ethics. This way they can feel part of the human society and its struggles. (Roth, 1969, p.13). Lea Goldberg, quoting Prince Mishkin, the protagonist of Dostoyevsky’s Idiot, insists that “You can tell children everything, everything indeed”. The pedagogical question, however, is how is that done. (Goldberg, 1977, p. 125).

Children’s stories, with their plots, messages and artistic presentation may not only interest children. Sometimes CL is written with more than just the child in mind. Writers want their works to be liked and approved by the adults: parents, teachers, and librarians, who all provide literature to children. Writers struggle, consciously or unconsciously, with the problem of writing for these two very different addressees, “because of the contradictory necessity of appealing to both…” (Shavit, 1986, p. 41). While determining the complexity, structure, stylistic level and the subject matter of the story, authors have to take into consideration these two potential readers. The results may be found on a continuum between two extremes, the one in which the writers “wink agreeingly to the adults and ignore the child” (Astrid Lindgren as quoted in Shavit, 1986, p. 42), and the other in which the popular commercial CL ignores the adults all together and caters only to the young readers (Shavit, 1986). Writers of a good number of works on this continuum though, beloved by children and adults alike, have found the right balance in creating works that appeal to both groups. They present sincere values or address psychological or social issues that are troubling to any age group. They use themes, structures and language to be grasped intuitively by the child and more intellectually by the adult. They use humour for the child, and at the same time offer the adult parodies or hidden jokes as a bonus. In books of CL like in many works of adult literature, a text can be layered, understood and realised in different ways by different readers. Dr. Seuss’s The Cat in the Hat is an excellent example. It is greatly enjoyed by children for its plot, illustrations, humour and language juggling. The story reflects the child’s inner tension between obedience and rebellion, between following rules and creative anarchy. Children may only intuitively sense its resonance with their unconscious inner struggle. An adult, on the other hand, may read the story on a different level, see the cat and the fish as reflections of the child’s inner polarity, the child narrator’s jump into action as the immergence of self discipline, and the orderly ending as the ideal balance between passions and norms.

Addressing two or even more groups of consumers (different age groups, different levels of familiarity with North American popular culture, etc.), is common in popular animated movies (Jungle Book, Lion King and Shrek, to name just a few). Often sophisticated and well executed, such movies succeed in entertaining the children without losing their accompanying adults and in fact drawing more adult viewers without the excuse of accompanying children. Their creators do so consciously, offering works that are based on visual, verbal and even musical layers, double meanings, allusions etc. Such movies are interpreted on different levels by the child and the adult. Children are entertained by the ‘overt’, simpler story, while the more knowledgeable adults enjoy the messages addressed at them, identifying the many ‘hidden’ stories and appreciating the parodies (Elkad-Lehman, 2003).

Ambivalent literature, such as Alice in Wonderland, The Hobbit, Winnie-the-Pooh or The little Prince, is discussed thoroughly by Zohar Shavit. These works, she claims, supposedly belonging to the children’s literary system, are deliberately written as ambivalent texts targeting two groups of implied readers, children and adults. In these books, the child may be only the pseudo addressee, where as the real reader targeted is in fact the sophisticated adult. This is done by employing at least two coexisting models, one more conventional for the child, and the other less established or innovative for the adult. Different reading habits and norms of the two groups allow for the full realizations of such a text on different levels. As a result “the writer not only enlarges his reading public… but also ensures the elite’s recognition of the dominant status of the text in the canonized children’s system… and his status in the literary system…” (Shavit, 1986, p. 68). By proceeding this way through the peripheral children’s literary system, writers manage to introduce into the general literary polysystem new models previously rejected by the adult canon. The acceptance of their works into the children’s canon allows eventually for the acceptance of their innovations further into the adult literary systems (Shavit, 1986, chapter 3).

Whether deliberately written primarily for the adult, or masterfully written especially for the child with further deeper insights for the adult to enjoy, many works in CL are good and satisfying reading material for the mature reader. It can therefore, be a good additional source of authentic material for the additional language learners of all ages.

5. Hebrew Children’s Literature

Hebrew CL also includes many excellent works enjoyed by children and adults alike. It can therefore be a good source of material for adults at any level learning Hebrew as an additional language. Throughout its young history, of less than a century, Hebrew CL has clearly reflected many aspects of the changing society which produced it and the young generation it has addressed. Hebrew CL includes depictions of ancient Jewish history, more recent Zionist and Israeli history, social issues, ethics and religious beliefs, different ethnic traditions, science and nature, and even competing values and ideologies.

What has established itself as Hebrew children’s classics, (a corpus still evolving,) are poems and stories that are considered the basic building blocks of every Hebrew speaking child’s acculturation. Poems and stories by writers from the first half of the twentieth century to more recent decades are not only read to and by children, they are also sung, played in theatres and intensively listened to and watched on screen at home. They are quoted, alluded to, parodied; and are the sources of common expressions even among adults.

However, despite a growing number of good books for children written and published today, there has been, in the past few years a new trend in which some of the old Hebrew children’s classics , that have stood the test of time, are being republished. Having already acquired high literary status, as part of Israeli cultural wealth, they are readily bought, and at times even reach the best-seller lists. They answer a need for Hebrew readers, who not only want to pass their old favourites to their children and grandchildren, but also want to enjoy themselves reading (Dar, 2005). Indeed, critics regard the canon of Hebrew CL as part of the general Hebrew literary canon.

The classics of Hebrew CL are not only by authors and poets who have written only for children (i.e., Levin Kipnis, Miriam Yalan Shtekelis), but also have some of the most famous adult canon writers (i.e., Hayim Nahman Bialik, Lea Goldberg, Nathan Alterman and Avraham Shlonsky) who in the first half of the twentieth century dedicated some of their creative endeavours to children. They engaged enthusiastically in what was at the time pioneering writing for young readers and listeners.

Hebrew CL was acknowledged as one of the most effective means for the revitalization of the Hebrew language and culture in modern times (Bialik, 1932). It therefore received a lot of attention from writers, publishers, educators and parents who were attempting to fill the almost empty bookshelves of Hebrew-speaking children. Thus, translations from world CL, as well as original writings, have contributed through the younger generation to the enrichment of the still evolving, revitalized Hebrew, with vocabulary and ways of expression more suitable for modern times.

There is no doubt that the impetus of this literature was the creation of pleasurable reading material for children, which would provide new vocabulary and language not yet in use among the first generations of Hebrew speakers. In addition, its content meant to impart gradually “all the creative wealth of the nation” but in an artistic way that would appeal to the child (Bialik, 1932). Thus, Biblical and rabbinic stories were sources of content and inspiration together with themes relating to modern times. Up to the mid twentieth century, Hebrew CL was influenced by the tendency within Soviet children’s literature, to impart through literature, national ideals and educational values. Other Hebrew writers, such as Lea Goldberg insisted on the humanistic, aesthetic aspects of children’s literature as the most important ones (Hovav, 1977, p. 17). Gradually the focus has shifted from the national to the personal. The educational aspect, with emphasis on the individual, was thus advocated later on by Miriam Roth: “Excellent literature educates. Not by morals patched and an ‘educational’ finger wagged. What makes it ‘educational’ is its deep human content offered in an excellent artistic form. Children learn a lesson from the fate of others, expand their view of the world, improve their language, enrich their ability for expression, and upgrade their ability of moral judgement. In short, they are educated in the light of excellent literary works” (Roth, 1969 p. 17).

Hebrew CL is varied. Some stories revolve around Jewish holidays, traditional values, and Jewish history. Others reflect events and ideologies in the history of the Zionist movement and the state of Israel, depict social tensions or deal with ethical issues. Hebrew CL engages in children’s psychological problems, answers to their curiosity in learning about the world around them and certainly offers entertainment , as well.

The lower status of the writers for children in the past, described in the previous chapter (Shavit 1986, pp. 38-39), does not seem to have been the experience of Hebrew writers for children. It may even be that the high standards and high prestige set for Hebrew children’s literature from the nineteen thirties on, has encouraged further generations of adult Hebrew literature’s best writers such as AmosOz, Yehudah Amichai and David Grossman to write for children, together with other excellent writers who have dedicated their work only to children (i.e., Miriam Roth, Lea Naor, Datya Ben-Dor, Shlomit Cohen-Assif).

The language of Hebrew CL varies greatly depending on its periods, themes and writers. It ranges from the highly literary to the colloquial. Much of it is masterfully written as befitting a literary tradition established by the above mentioned literary giants. Considered one of the means of revitalizing the Hebrew language among the younger generations, CL has drawn on the language of ancient texts (Biblical, Rabbinic and later). The ancient language however, has been modernized in an attempt to create a vibrant new vocabulary and ways of expression, by which children could communicate. The conscious attempt to enrich children’s language through literature continued even after Modern Hebrew was well established and secure. Therefore, difficult vocabulary and literary language in general have not been necessarily avoided. Lea Goldberg claims that children absorb a text as a whole, including unfamiliar words. Literature eventually develops the child’s sense of language and lays the foundation for expression and style (Goldberg, 1977, p.68).

The range of registers in Hebrew children’s literature today is wide. A rich vocabulary, has been characteristic of Hebrew children’s literature at its onset. With the development of modern conversational Hebrew, a more lively and flexible repertoire and various registers have also developed. Writers have had more choice, and with changes in writing norms, they have been also able to use of simpler language, even the colloquial. (Still, it would be interesting to compare and check if, due to historical circumstances, recent Hebrew literature for young children does include works written in more demanding literary language than would commonly be used in similar literatures of other languages. If so, it may be due also to the reliance of Hebrew writers for young children on the fact that Israeli children are exposed from early age to considerable dosages of texts in literary registers (i.e., listening to much of the still best selling ‘classics of children’s stories, poems and songs, familiarity with classical vocabulary connected with Jewish holidays and traditions, encounters with the original Biblical texts from grade two, etc.). Hebrew CL has been written in a wide variety of styles and registers, and can provide ample linguistic examples reflecting, to a large extent, the language use in writings for adults.

Not uncommon in Hebrew CL are works inspired not only in language but also in content by Bible stories, their midrashic interpretations, rabbinic stories, and folktales from the various Jewish Diasporas. These are sources upon which Hebrew modern writers for children draw to create their new works. For children, such modern works are to a large extent their first encounter with formative Jewish stories and figures. Ancient stories thus, are retold through innovative, creative interpretation (i.e., Meir Shalev’s or Ephrayim Siddon’s Bible stories), continuing two millennia of midrashic tradition. As will be demonstrated later in this paper (see chapter 8), it is not unusual to detect in modern children literature numerous lexical, stylistic and thematic allusions borrowed from the ancient Jewish texts. These common occurrences of intertextuality are not necessarily meant for, or always clear to the children, but certainly provide them with taste of the language and its culture. Knowledgeable adults reading the same material are able to detect such layers, thus adding deeper meanings and richer texture to the text.

To conclude, Hebrew CL is an important system within the Modern Hebrew literary polysytem. Much of it can provide both the child and the adult reader with a rewarding reading experience, enjoying all of its language, style and content.

6. The Potential of Hebrew Children Literature for the Adult Second/Foreign Language Student

Chapter 3 discussed the integration of children literature into the L2 curriculum. Hebrew CL, with its specific history and characteristics, has even greater potential for adults studying Hebrew for the pursuit of their roots, familiarity with the Jewish tradition and connection with Israel.

Current Israeli immersion textbooks, with their pragmatic orientation, include few children’s poems, but only as enriching material, not as an integral part of the curriculum. Ulpan Milah in Jerusalem, which offers a variety of Hebrew courses with cultural content, offers olim (new immigrants), a short six hour course dedicated to children’s literature which “addresses problematic gaps that may arise between olim parents and their children, learning in the Israeli educational system. The chosen texts represent the connection between children’s literature and common forms of expression found in day-to-day speech familiar to all Israelis” (Milah, 2005). The value of this CL as an authentic reflection of society is acknowledged, but it is used only to familiarize a limited group of learners with their children’s new world. CL is not used for the sake of the adult learners themselves.

Hebrew children’s literature is an important dynamic system in the Modern Hebrew polysystem. It is widely consumed in its written, staged, filmed and sung forms. Hebrew CL not only acculturates the Hebrew speaking children into their society, but contributes considerably to the basic images and idioms accompanying every Hebrew speaker from childhood into adulthood. Its content and language keep echoing in written or oral texts addressed to the adults, whether in conversation, advertisement, popular music, non fiction or fiction publications. This is done in various manifestations of intertextuality: borrowing, imitations, citations, manipulation etc. Not surprisingly, even a simple Google search of any ‘classic’ CL titles, or famous lines from them, produces an interesting variety of intertextuality in texts related to consumerism, career searching, tourism, social, political and psychological issues, and so on. Introducing an adult learner to some of the ‘musts’ in Hebrew CL is a good way to familiarize them with some of the basic elements of Israeli culture.

Much of Hebrew CL is inspired by classical Jewish texts in both form and content (see chapters 5, 8b.& 8d.) Biblical and rabbinic idioms and imagery are often found not only in religious contexts but also in day to day conversations, news, popular music, fiction and non-fiction, be it sophisticated or popular. Introducing Hebrew CL literature, which thus echoes the classical sources to the adult Hebrew learner is a good introduction to textured texts of Modern Hebrew which keeps drawing upon its roots.

Depictions of Israeli society in Hebrew CL may provide the adult learner of Hebrew with glimpses of the country, its people and its culture. Just as Hebrew CL, through its short history, has been one of society’s most effective tools to pass its values and cultural patterns on to its younger generation, so it can give the adult reader an idea about social, ideological and political changes reflected in it (Gonen, 2005). One can learn about such developments and value shifts even through the works of one writer (Elkad-Lehman, 2003). Ruth Gonen, who reviewed illustrated Hebrew children’s books from 1948-1984, found in them a gradual shift from recruited literature, and its focus on the collective and its national issues, to a more open, child-centred approach. Among the value categories she examined were: creativity and humour, study, materialism, industriousness and courage, Jewish tradition, growth, happiness, family, law and order, friendship and peace, patriotism, nature, individualism, sensitivity and social criticism (Gonen, 2005). Dealing with any of these values through CL in the adult classroom can certainly allow students deeper insights into Israeli society as well as provide them with opportunities to compare between cultures and develop discussions.

Relatively short works of Hebrew CL can also be used as a stepping stone to adult literature (Ho, 2000) whether they are adapted or not. The next stepping stone for motivated students towards the end of Bet level may be books of the Gesher series published by the Jewish Agency Education Department. The series includes both fiction and non-fiction for adults and young adults, adapted from the original Hebrew works, with vowels added, as well as translation of key words. These texts are not meant for intensive reading but encourage the students to read fluently and get the main content without analysing every lexical and grammatical item, thus, familiarizing themselves and absorbing the characteristic ‘behaviour’ of the new language. This series is a good introduction to Hebrew writings of various genres, and a gradual entrance to reading longer texts.

As mentioned above, (chapter 5) some of the best works in Hebrew CL literature were written by renowned authors who also wrote for adults. Reading their works of CL in the lower level adult Hebrew class is a good opportunity for the teacher to tell students about the place of these writers within the adult Modern Hebrew canon. The teacher may want to encourage the students to read works by such writers, for the time being, in their first language, and through them start learning about the Israeli literary scene. Works by literary writers are included in the Gesher books series and could be recommended for students at the end of level Bet, with the hope that they will progress eventually and will be able to read the original in the future.

Thus, Hebrew CL can provide pleasurable, effective material to the adult Hebrew classroom, even in the beginner and lower intermediate levels, and support language learning. It can give students a glimpse into Jewish traditions, adult Hebrew literature and Israeli history, society and culture. Familiarity with good Hebrew CL may create the motivation to read further independently and progress gradually to more challenging literary texts. Story Time at the Vancouver Mini Ulpan described in the next chapter is an attempt to introduce Hebrew CL at the lower levels of Hebrew as L2.

7. Story Time in the Vancouver Mini Ulpan

Three of the four stories presented in this paper have been used as an important part of the curriculum at the Vancouver Mini Ulpan and have always received very positive response from students. The Vancouver Mini Ulpan consists of three immersion non-consecutive courses (25 hours in 5 days each), offered in small classes. The levels offered to date are Aleph (Beginner), Aleph Plus (Mid Beginner) and Bet (Lower Intermediate). Each should be regarded as an intensive introduction to the specific level, requiring further study for the slow ‘digestion’ of its content and completion of the level in weekly classes offered. The way Story Time is implemented in the Mini Ulpan does not suggest that this is the only method or the ideal framework in which children’s literature can be used in L2 teaching and learning. It is certainly possible that experimenting with such material in the more expanded framework of Ulpan courses, or the more limited weekly classes, could produce good results. Each framework requires appropriate adjustments in order to integrate the material into each program with its particular objectives, time, span and pace. There is no doubt that CL has a great potential for the teaching of children studying L2. The way it should be used with different young age groups has to be specifically tried and studied.

The program of the Vancouver Mini Ulpan for each of the three levels includes: singing, conversation, grammar, story time, video watching, games, optional Hebrew window shopping at the local mall and for the higher level, a visit to local Israeli restaurant (ordering and service in Hebrew). The idea is to teach grammar and vocabulary in context. Elements taught and practiced in each lesson of the Mini Ulpan hours are constantly referred to and reinforced in the others. For example, the songs sung in the morning are chosen carefully to reflect the grammatical subjects taught that day. Thus, when the particular grammatical subject is introduced later in the day, students are reminded of the corresponding song, sing it again, and go on to apply that grammatical subject in conversation. Later, at story time, that same grammatical subject may occur again and the students’ attention is drawn into it. During story discussion, attention is paid to proper use of those grammatical items learned earlier in the day. The same is done with vocabulary emphasised in each level. Even lunch time, spent usually with the teachers, (in a relaxed English/Hebrew conversation), presents many opportunities to tie different lexical, grammatical and thematic elements together.

Story time occupies the last of the five hours of the Mini Ulpan day. The stories are chosen so that they are compatible with, and can reinforce the grammar and vocabulary introduced and reviewed in each level. The story is divided into five, relatively short passages/chapters to be delivered through the five study days.

However, other than answering to the pragmatic requirements of compatibility with material taught, these particular stories are chosen first and foremost because they are good stories. It is also worth mentioning that I personally liked them very much and therefore have been able to present them enthusiastically to the students. I feel that this is an important subjective point to emphasis, especially for story time situations. Teachers’ enjoyment of a story is contagious and can create an exciting fun atmosphere which, I believe enhances students learning and retention of the material learned.

In each session of story time, the teacher reads aloud the daily chapter. The students are asked not to follow the text during the first reading. They are expected to concentrate on listening .The first time, the daily chapter is not necessarily read exactly as in the text. The teacher stops often to point to the illustrations, point to objects around the classroom and out the window, use expressive body language and tone, paraphrase and explain, and refer to vocabulary used in earlier hours of the study day. English is used rarely and only as a last resort. All this is done while constantly ensuring students’ comprehension of the storyline. Following this first expanded presentation, the teacher reads the text aloud for the second time in the same animated way pointing to illustrations, but with less explanation. This time students follow the text and in Aleph and Aleph Plus levels even join the teacher in reading it aloud.

This part of story time, even though not participatory, is extremely important. Story time allows the students to sit back and enjoy a work of literature. They are exposed to an input of the new language, but are not under the pressure of having to produce an output in it. The text they listen to and watch being presented is: meaningful (real story), authentic (not written originally for L2 teaching purposes, as well as read and well pronounced by a native Hebrew speaker), as well as comprehensible. This are the three qualities expected from an effective input in order to enhance L2 acquisition and ensure a better output in the language learned later on (Krashen, 1982). No time is dedicated in class for independent reading by the students. They are expected to reread the text at home and re-listen to it read (on the CD provided).

In general, the students are encouraged to relax, not worry about every singular word or every single grammatical phenomenon they encounter. Rather, they are expected to try and capture the general meaning and follow the story line. The various extra-textual means used, allow them to gradually construct their schema before approaching the written text. It might be worth reminding students that as children in their first language they were open enough to construct the meaning of anything they heard or read, even if it contained words not yet familiar. This is the way they built their first language vocabulary. In fact, though to a lesser extent, as adults, they keep doing so, when constructing the meaning of what they hear or read in spite of possible ‘disturbances’: missing words, and the occasional unknown words. Some L2 adult students tend to lose confidence when they do not understand every single word and structure read or listened to in the new language. This is not an efficient language learning approach. It is important therefore to encourage them to venture at making an ‘educated guess’ with the help of context, schema, and familiar forms, which give partial information (i.e., tense, person, gender or familiar roots in unknown forms etc.). Story time is therefore an excellent medium for the development of such strategies which then lead to increased confidence.

After listening to the story at least twice, the students start retelling the story, prompted by the teacher’s guiding questions, and with the illustrations in front of them. Alternately, illustrations (photocopied, mounted on large cards and laminated) are used by every two students to retell the story to each other.

A discussion of subjects stemming from the passage follows the reading. The extent of the conversation varies, starting from the actual story and expanding in order to be applied to the students’ world and background. The discussion ranges from concrete subjects (weather, home, work etc.) to more general issues (social, psychological, moral, etc.), depending on the group’s level, group makeup, creativity and interests as well as time constraints. In Levels Aleph Plus and Bet, students are also provided with basic discussion expressions: ‘I think that…’ ‘I agree with…’, etc. The teacher repeats and summarizes the information and ideas offered by the students in a correct manner, as well as soliciting further feedback from the class: ‘He/She says that…. ‘What do you think?’ ‘Do you agree?’ The repetition and summary of participants’ contribution by the teacher not only highlights the information and ideas expressed, but presents them in a clearer more normative way, which is easier for the others to comprehend. Again, this is a meaningful and comprehensive input presented through the teacher in an authentic voice. Corrections, or expected self corrections, are limited mostly to the lexical and grammatical subjects, central to the particular course. Otherwise, more emphasis is given to encourage participation.

Students who try to express an idea beyond the linguistic scope of their level are helped if possible by offering them level-appropriate lexical and grammatical options. Students are advised though, to adopt general ‘simplifying’ strategies in order to produce the best approximation to what they want to express. They are shown that breaking a complex message into shorter, simpler sentences, grammatically and lexically level-appropriate, without loosing its essence, is often possible. Thus, to avoid frustration, a student is allowed at times to summarise his/her complex idea in English and the teacher (together with the class) try to suggest the simplified Hebrew alternatives. It is important to stay within the level appropriate grammatical boundaries. As for the vocabulary, one can be more flexible and offer more accurate words, if needed, even beyond the controlled, most frequent vocabulary of the specific level. An ability to ‘translate’ a sophisticated and complex idea into simpler discourse is a skill to be learned, important especially for students of the lower level FL/SL. Good children’s literature with the variety of adult appropriate issues they offer for discussion, can be a good medium in which effective strategies can be practiced.

The next day, story time starts with the students, in turns, retelling the story so far with the help of the illustrations. The teacher then repeats the reading of the previous chapters, before adding the new portion in the same way described above. The story is completed on the fifth and last day of the course. If a video of the story is available, it is watched at this point of conclusion. Continuous repetition of familiar portions of the story every day help the students apply much of what has been learnt during the course as a whole and provide a sense of mastery and completion.

The Mini Ulpan program relies heavily on frequent vocabulary. As explained above (chapter 3), it is not surprising to find a great overlap between words learned throughout the program and those encountered in the story presented. Frequency in every word category (verbs, nouns, adjectives etc.) is indeed one of the most important considerations when planning a L2 language course. Developing familiarity with frequent vocabulary allows for ample opportunities to refer to it and to apply it in the various parts of the day. It also expands students’ passive and active repertoire and allows for better comprehension and participation during story time.

As familiarity with the Hebrew verbs is deemed essential to any of the Mini Ulpan levels, great attention is given to teaching and reinforcing their forms and grammar (always in context) in earlier hours of the course day. Level Aleph concentrates on the present tense (participle) and the infinitive, level Aleph Plus concentrates on the past tense, and level Bet concentrates on the future tense. At any of these levels, frequent verbs from the five major stems (בנינים) and the various root groups are presented. As with the general frequent vocabulary, there is of course a considerable overlap between the verbs presented in every level and those appearing in the story. The following numbers depict the makeup of each level’s verb list:

- Aleph (Beginners):

A. 28 most frequent verbs presented during the course.

B. 20 story (ואז הצב בנה לו בית / Ve’az Hatsav Banah Lo Bayit) verbs, all of which are frequent verbs.

C. 20 (100%) of the story verbs are most frequent verbs.

At this level there are no story verbs which do not appear in the basic verb list of the course. In the next two levels, many more known verbs are reinforced and new ones presented, but the stories also contain new verbs which are not considered frequent verbs and students are not expected to retain them at this stage.

- Aleph Plus (Beginners Plus):

A. 63 frequent verbs are presented (whether new, or known and reinforced).

B. 33 story ( דירה להשכיר / Dira Lehaskir ) verbs

C. 22(67%) of the story verbs may be considered level-appropriate frequent verbs.

- Level Bet (Low Intermediate):

A. 100 frequent verbs are presented (whether new or known and reinforced).

B. 69 story ( איתמר מטייל על קירות / Itamar Metayel al Kirot) verbs

C. 49 (70%) of the story verbs may be considered level-appropriate frequent verbs.

In the three levels, there is considerable overlap between frequent verbs in the stories (C) and frequent verbs dealt with in the course as a whole (A):

Aleph (71%),

Aleph Plus (35%)

Bet (49%).

Thus, the three particular stories used for each of the Mini Ulpan levels support the learning of a large percentage of the verbs imparted, and hopefully their retention as well. Other stories that can be used may contain different verbs, but these would still overlap greatly with level-appropriate frequent verbs. While listening to the story, reading it and discussing it, the students encounter many of the frequent verbs they are expected to know. They are able to reinforce their familiarity with previously learned verbs, and then use them in discussion. For their convenience, the students are offered a comprehensive glossary of the story verbs in form of a partial-conjugation charts identical in format to the frequent verbs charts offered while studying the grammar earlier in the day.

As described above, the emphasis in these week-long intensive courses is on two of the four language skills. Listening and speaking are given first priority. Reading (not independently) is given some time in class. Students though, are expected to read and reread at home in order to ensure their intake of the material learned. However, because of time constraints, writing, deemed the last on the priority list in this framework, is not given any time in class. Written exercises are offered and recommended for homework, but are only optional. Indeed, much attention is given in these levels to massive meaningful, authentic and comprehensible input, assuming that it will eventually translate into better listening, reading and conversational skills, and that eventually, writing too, even though not treated in this framework, will be improved in following ones.

Only 5 out of the 25 Mini Ulpan hours are dedicated to story time. Longer courses may allow more time for this purpose and the exploitation of the story in different effective activities such as role playing, creative writing, discussions in pairs etc. The advantage of story time though, is the brief pleasurable exposure to a work of literature in the new language and the fostering of students’ openness and confidence to confront a text not closely read and understood. Therefore, during a longer course it might be more beneficial to expose the students to more stories, rather than to exploit the full potential of one. Stories will overlap differently with level-appropriate frequent words and basic grammar, as well as provide opportunities to learn, review, practice and help retain the material imparted. Wide daily exposure to a larger corpus of texts (listened to and read) has great merits in FL/SL language acquisition, not unlike daily story time at home and in school for young children during their first language acquisition.

8. Four Hebrew Children Stories

Three stories are already in use in the Vancouver Mini Ulpan and a fourth one is suggested for a future Bet Plus level (link below to: 8a, 8b, 8c, 8d). They were assessed for their use as additional material in teaching Hebrew to adults. The literary analysis included in their assessment is by no means comprehensive. Rather, it is meant only to point to the potential of using well selected children stories for the adult Hebrew (Second/Foreign/Heritage/ Additional Language) classroom. The complex nature of these stories, their styles, layers and the issues with which they deal provide ample opportunities for teaching and learning the language, encountering issues on an adult level, in spite of the elementary linguistic repertoire, gaining some insight into the studied culture, as well as enjoying a real work of literature. Also, the discussion concerning these stories and their way of presentation and use does not suggest that all that is offered can find its use in every adult Hebrew classroom or that it is an exhaustive analysis. Rather, what is suggested can be adapted to different frameworks, class makeup, interest, etc., as well as explored and developed further.

The discussion of the four stories revolves around the linguistic, technical and literary aspects. Much credit should be given to all past Vancouver Mini Ulpan students who have creatively used their restricted repertoire to express their insights on the stories, in addition to skilfully applying what they have learned to lively conversations in Hebrew.

8a. Level Aleph (Beginners’ level).

ואז הצב בנה לו בית… Ve’az Hatsav Banah Lo Bayit,

Written and illustrated by Avner Katz.

To read this chapter please click on ואז הצב בנה לו בית

8b. Level Aleph Plus (Mid Beginners’ level).

דירה להשכיר Dira Lehaskir,

written by Lea Goldberg. Illustrated by Shmuel Katz.

To read this chapter please click דירה להשכיר

8c. Level Bet (Low Intermediate level)

איתמר מטייל על קירות Imamar Metayel al Kirot

Written by David Grossman and illustrated by Ora Ayal

To read this chapter please click איתמר מטייל על קירות

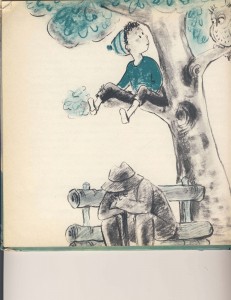

8d. Level Bet Plus (Intermediate)

יונתן וסבאקטן Yonatan veSabakattan

Written by Rivkan Elitsur, illustrated by Binna Gvirtz.

To read this chapter please click יונתן וסבא קטן

9. Conclusion

Literature can be an important and enriching component of the intermediate and advanced levels of L2 courses. Students in lower levels though, would have difficulty coping with its lengthy and complex make up as well as highly advanced vocabulary and grammar. For the beginner’s and the lower intermediate levels, children’s literature can be used. It should not be dismissed as a simplistic and inappropriate medium for imparting language for the adult student. Good works of CL offer the adult students artistic texts from the culture they are being introduced to, which are interesting, using themes suitable for all ages., Students will also thus have opportunities to use their emerging language skills in more challenging subjects, and of course, an excellent medium through which they can practice their basic vocabulary and grammar. Much of the rich and lively Hebrew children’s literature can be used and contribute to this process. It is sophisticated enough for adults appreciation. It can also greatly contribute to and complement the curriculum of lower levels (Aleph and Bet) ulpan programs. It can reinforce much of the material taught in these courses, allow the students to discuss a variety of universal, Jewish and Israeli topics, and expose the students to some of the important building blocks of Modern Hebrew culture. The four stories presented in this paper show the potential of Hebrew CL. A search for more suitable material from this literature is needed. It can, no doubt, constitute an excellent addition to immersion programs, which strive to offer the adult learner, not only an effective way to acquire a language, but also an exposure to its culture.

10. References

בנד, א. (1983-1986). עברית (שלב ב-ג). ניו ג’רסי: בהרמן האוס.

[Band, O. (1983-1986). Hebrew (Level 2-3). New Jersey: Behrman House].

ביאליק, ח.נ. ( תרצ”ב). לזכרו של ש. בן-ציון. בתוך: (תש”א). כל כתבי ח.נ. ביאליק. תל-אביב. דביר.

[Bialik, H. N. (1932). Lezikhro shel S. Ben-Tzion. In (1941). Kol Kitvey H. N. Bialik. Tel-Aviv: Devir.]

ביאליק, ח. נ. ורבניצקי, ח. (עורכים) (תרצ”ו). ספר האגדה (כרך ראשון, ספר שני) תל-אביב: דביר.

[Biealik, H. N. & Ravnitsky, H. (Eds.) (1936). Seffer Ha’aggadah (Volume 1, Part 2). Tel-Aviv: Devir.]

Bettlelheim, B. (1976). The uses of enchantment. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

כהן, א. ((1990). ספור הנפש – בבליותרפיה הלכה למעשה. כרך א. קרית ביאליק: הוצאת “אח” בע”מ.

[Cohen, A. (1991). Bibliotherapy. Kiryat Bialik: “Ah” Publishing LTD.]

דר, י. (2005). ספרות לילדים שהתבגרו מזמן. הארץ. 21 בדצמבר 2005. נשלף ב21 בדצמבר 2005 מ:

http://www.haaretz.co.il/hasite/objects/pages/PrintArticle.jhtml?itemNo=659718

[Dar, Y. (2005). Sifrut liladim shehitbagru. Ha’aretz. December 21, 2005. Retrieved December 21, 2005 from http://www.haaretz.co.il/hasite/objects/pages/PrintArticle.jhtml?itemNo=659718 ]

אליצור, ר. (1979). הארמון על ההר. תל-אביב: מסדה.

[Elitsur, R. Ha’armon al haHar. Tel-Aviv: Massada.]

אלקד-להמן, א. (2003). לסוגיית הספרות האמביוולנטית – התבוננות בשלוש יצירות מאת נורית זרחי. עיונים בספרות ילדים, חוב’ 13, עמ’ 5-46.

[Elkad-Lehman, I. (2003). On the problem of the ambivalent literature – a look at three of Nurit Zarhi’s works. Iyunim besifrut yeladim, 13, 5-46.]

Even-Zohar, I. (1990). Polysystem theory. Poetics Today, 11:1 (pp.9-26).

Flikhinger, G. G. (1984). Language, literacy, children’s literature: The link to communicative competency for ESOL adults. Paper presented at the International Reading Association (IRA), Texas State Council. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 268 504)

גולן, מ. (1983). קריאה כהרפתקה – ספרות באמצעות דרמה יצירתית. תל-אביב: ספרית פועלים.

[Golan, M. (1983). Kri’ah keharpatkah. Tel-Aviv: Sifriyat Po’alim.]

גולדברג, ל. (1977). בין סופר ילדים לקוראיו. תל-אביב: ספרית פועלים.

[Goldberg, L. (1977). Beyn sofer yeladim lekor’av. Tel-Aviv: Sifryat Po’alim.]

גולדברג, ל. (1986). דירה להשכיר. תל-אביב: ספרית פועלים.

[Goldberg, L. (1986). Flat for rent. Tel-Aviv. Sifryat Po’alim.]

גונן, ר. מסרים ערכיים בספרי-ילדים ישראליים מאוירים לגיל הרך בין השנים 1948-1984. הגיל הרך. נשלף בדצמבר 24, 2005 מ http://www.gilrach.co.il/article.asp?id=374

[Gonen, R. Messarim erkiyim besifrey yeladim yisraeliyim me’uyarim lagil harakh beyn hashanim 2948-1984. Hgil Harakh. Retrieved December 24, 2005, from http://www.gilrach.co.il/article.asp?id=374 ]

גרוסמן, ד. (1987). איתמר מטייל על קירות. תל-אביב: עם-עובד.

[Grossman, D. (1987). Itamar walks on walls. Tel-Aviv. Am-Oved.]

הרמתי, ש. (1983) הבנת הנקרא בסידור ובמקרא. ירושלים. המחלקה לחינוך ולתרבות תורניים בגולה של ההסתדרות הציונית העולמית.

]Haramati, S. (1983). Reading the Bible and the prayer book with comprehension.

Jerusalem. The Department for Religious Education in the Diaspora. The World Jewish Agency.]

חייט, ש., ישראלי, ש., קובלינר, ה.(2000-2001) עברית מן ההתחלה (א-ב). ירושלים: אקדמון.

[Hayyat, S., Yisraeli, S. & Kovliner, H. (2000-2001). Ivrit min hahat’halah (vols. 1-2). Jerusalem: Academon].

Ho, L. (2000). Children’s literature in adult education. In Children’s Literature in Education, 31 (4), 259-271.

חובב, ל. (1977). תורת ספרות הילדים של לאה גולדברג. בתוך: גולדברג, ל. בין סופר ילדים לקוראיו. (עמ’ 9-51) תל-אביב: ספרית פועלים.

[Hovav, L. (1977). Torat sifrut hayladim shel Lea Goldberg. In Goldberg, L. Beyn sofer yeladim lekor’av. Tel-Aviv: Sifryat Po’alim.]

כץ, א. (1979). …ואז הצב בנה לו בית. ירושלים: כתר

[Katz, A. (1979). …and then the turtle built himself a House. Jerusalem: Keter.]

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Milah – The Jerusalem Institute for Education. Seminars and Courses in Easy Hebrew. Retrieved December 24, 2005, from http://www.milah.org/index1.htm

Omaggio Hadley, A. (2001). Teaching language in context. Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Onestop Magazine. (2005). Using Literature in teaching English as a foreign / second language (1). Retrieved 31 October 2005, from http://www.onestopenglish.com/News/Magazine/Archive/tefl_literature.htm

Onestop Magazine. (2005). Using Literature in teaching English as a foreign / second language (2). Retrieved 31 October 2005, from http://www.onestopenglish.com/News/Magazine/Archive/esl_literature.htm

רות, מ. (1969). ספרות לגיל הרך. תל-אביב: אוצר המורה.

[Roth, M. (1969). Literature for young children. Tel-Aviv: Otsar Hamoreh].

Shavit, Z. (1986). Poetics of children’s literature. Athens and London: The University of Georgia Press. Retrieved July 19, 2005, from http://www.tau.ac.il/~zshavit/opcl

Smallwood. B. A. (1992). Children’s Literature for Adult ESL Literacy. National Clearinghouse on Literacy Education Washington DC. ERIC Digest. ED353864 1992-11-00.

Uveeler, L., & Bronznick. N. B. (1972). Ha-Yesod. New York: Philipp Feldheim Inc.

וייס, י. ועבאדי, ע. (2003). טיפוח כשירות לשונית באמצעות קטעי הומור מיצירת חנוך לוין. בתוך: הד האולפן החדש. 86. 5-18. נשלף ב 22 בנובמבר 2005 מ

http://207.232.9.131/adult-education/hed_haulpan86.htm

[Weis, Y., & Abadi, A. (2003). Tipuwah kashirut leshonit be’emtsa’ut kit’ey humor mitsirat Hanoch Levin. In Hed Ha’ulpan HeHadash 86. 5-18. Retreived November 22, 2005 from